Thursday, December 9, 2010

Update: English tuition hikes

Students surrounded a Rolls Royce carrying Prince Charles and Camilla tonight, and attacked it in protest against the tuition hikes. Here's a story about it.

More on tuition increases in England

It's been a busy autumn in England for the higher education sector. Lord Browne finally released his review committee's recommendations for reforming the student fee system (the full report can be found on the Browne Review website). The Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government quickly follow-up with its plan, which adopted many of the Browne recommendations but added some of its own, including a proposal to cut funding to universities (the rough analog of state appropriations in the U.S.) by roughly 40% over the next four years. The £3 billion pound cut is part of a larger, £83 billion cut in all government spending designed to help restore the British budget deficit to a more reasonable position.

Today, the Parliament passed a key component of the Government's plan: an increase in the fee cap from the current level of £3,290 to as much as £9,000, or about $14,000, in the fall of 2012. This is designed to offset the government funding cuts by shifting the burden of financing to students. From the release of the Browne Review committee, through to the Government's proposal, and on to Parliament's vote today, students have been protesting the funding cuts and fee increases. The picture above shows a protest organized by the National Union of Students in response to today's vote (see my blog post on fee protests that occurred while I was on sabbatical in London).

Once I get out from under the end-of-semester crush, I'll be writing more about how student financing is changing in England, and the implications these changes are likely to have on students and universities there.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

$42 million for the CEO of Strayer Education Inc.

Bloomberg reported yesterday that the chairman and CEO of Strayer Education, Robert Silberman, was paid $41.9 million in compensation last year. Or, as Bloomberg put it, "That’s 26 times the compensation of the highest-paid president of a traditional university." Bloomberg went on to note that Strayer receives three-fourths of its revenue through federal student loans and grants. And Silberman is not the only executive in the proprietary sector receiving this kind of compensation; the Bloomberg article indicates that Charles Edelstein, co-CEO of the Apollo Group (corporate parent of the U. of Phoenix, the country's largest postsecondary institution) received $6.5 million in compensation last year.

Compensation of executives of for-profit education companies has been in the news of late, with all of the focus on this sector and its dependency on revenues through federal Title IV funds. Much of Silberman's compensation was in the form of stock options granted last year, so it's not as if he was paid the $42 million in salary. Nevertheless it is tempting to compare Silberman's compensation - and his responsibilities - with the heads of other postsecondary institutions.

Here's a comparison of Strayer, Penn State, and the State University of New York system (all figures are for FY2009):

| Strayer | $512 million | 54,300 | 87 | $41.9 million |

| Penn State | $4.042 billion | 92,613 | 24 | $642,760 |

| SUNY | $8.456 billion | 218,528 | 64 | $654,996 |

You can draw your own conclusions.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

The problem of comparing student loan repayment ratios across colleges

Earlier this year I published a post about Businessweek's ridiculous attempt at ranking colleges based on the return on investment students earn from attending the institution. I listed the problems with Businessweek's methodology, many of which were based on its decision to use data on salaries from a firm called PayScale, which invites people to complete an on-line survey and post information about what college they attended, their major, what they earn, etc. Beyond the obvious problems with data like these being collected non-randomly, using data like this to come up with a single measure for the return on investment of a college education makes absolutely no sense at all. If you don't want to read my entire post, here's the key part of my conclusion:

Most of the evidence from labor economists (see the work of Card and Krueger, or Ehrenberg) points to the fact that differences in returns to college are driven more by within college variation (i.e., differences in the choice of majors or academic experiences once enrolled in a particular college) rather than differences between colleges. What this means is that the decisions students make about what to major in, what courses to take, and what other experiences they have in college have much more influence on their post-college earnings than does the choice of which college to attend.And now another website, called CollegeMeasures.org (sponsored by the American Institutes for Research), is using the same PayScale data to come up with ratios of student loan payments to earnings for individual colleges. CollegeMeasures has a very good intent - to try to provide institutional officials and policymakers with more information about the outcomes related to higher education. The website's stated purpose is:

. . . to provide measures of performance for four-year colleges to the trustees and state government officials who are responsible for their success. Our goal is to present measures that are informative and thought-provoking, using the best data available. The data are collected from widely-respected sources and represent the best of what is available at the current time.It repeats information available from many other on-line sources on things like first-year retention rates and graduation rates. It also calculates some other measures from publicly-available data, including a cost to produce each undergraduate degree and an annual cost per student. And it then ranks each institution compared to all institutions, as well as all institutions in its own sector (public, private not-for-profit, or for-profit).

I want to reiterate that the CollegeMeasures website has good intentions. But its attempt at calculating ratios of student loan payments to earnings is, I am afraid, likely to be of little if any value to policymakers, institutional leaders, or even consumers. There are plenty of caveats about the data used in the fine print of the website, but I doubt most readers will get that far. The basic issue is that coming up with just one measure for this ratio requires the use of average (or median) student loan and earnings data. And the problem is that both of these measures are likely to have very broad distributions on any one campus, thus making a single measure - used to compare across all institutions in the country - of little or no value at best, and entirely misleading, at worst.

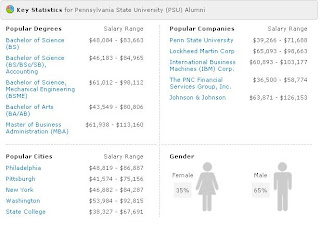

Let me use my own institution, Penn State's University Park campus as an example. You can see PayScale's salary data for the campus on its website. Here's an excerpt (you can click on an image to enlarge it):

It's unclear from the PayScale website whether these are the only salary data they have on Penn State graduates, or whether this is just a sample. And similarly, you can't tell from the CollegeMeasures website which PayScale data they use in calculating their loan repayment ratios, other than they say they are using median salary for people with five or less years of experience. But look at the salary ranges shown in the graphic above -- they are huge. In some cases, the student loan repayment ratios for students at the top end of the salary range would be less than half that of students whose salaries are in the bottom end of the distribution. So which one is the "best" repayment ratio on which to base a decision to attend Penn State or on which to judge Penn State's performance? We have no way of knowing.

There are obviously large problems with the non-random sample nature of the PayScale salary data. For example, you cannot tell who's completed their survey, and how representative they are of all Penn State's graduates. Another problem can be clearly seen in the graphic above, which shows that 65 percent of the PayScale data come from men, and 35 percent from women. But according to data from the U.S. Department of Education's IPEDS Data Center, 46 percent of bachelor's degree recipients at Penn State's University Park campus in the 2008-09 year were women. Given that men and women are non-randomly distributed across different majors, and that the earnings of men and women are quite different, the PayScale data for Penn State are clearly biased toward men.

Clearly, coming up with good measures of the return-on-investment of attending college is a difficult task. There are too many individual variables that affect the calculation, and attempts to simplify the process by coming up with a single measure - and then using that to compare across institutions - do not help us understand anything about institutional performance.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Rising health care costs hit home

The rising cost of health care is one of the public policy topics that probably receives more attention in the press than the rising cost of college, the latter of which I know a lot more about. For almost 30 years I've worked at universities almost without interruption, and the five years I wasn't working at a university I was covered by my wife's health insurance under her union contract as a teacher, which was similar to what I received as a university employee. Having worked in universities and benefited from the very generous benefits many universities offer, I've been largely protected from the challenges that many families face in gaining access to and paying for health care. I recognize that not all higher education institutions offer such generous benefits, but the ones at which I've worked have had very good coverage.

For example, the current coverage at Penn State (which self-insures its employees) costs me $247.62/month for coverage for our family. As a benchmark, I have a close friend who is my age and self-employed, and has to buy insurance for himself. He pays over $500/month just for individual coverage that is nowhere near as comprehensive as I enjoy as a Penn State employee. And for my monthly premium, the coverage my family receives is close to universal; we pay small ($10-$20) co-pays for office visits, and beyond that, most office visits for primary care physicians, specialists, hospital stays, procedures, etc. are covered in full. There are of course exceptions; you do pay more if you go outside the approved network of providers (20% of the cost), but the network is fairly inclusive of health care providers, at least in our area around State College. We also have relatively good prescription drug coverage. Many preventive procedures are free.

As an example, a couple of years ago, our youngest daughter was in the local hospital for four days. She had no surgeries or unusual procedures, other than a X-ray or two. The bill came to over $15,000, and we paid nothing other than a $50 co-pay for our emergency room visit before she was admitted to the hospital. This comprehensiveness of the coverage is similar to, and priced in roughly the same ballpark (adjusting for health care inflation) to what I enjoyed when I worked at MIT and at the University of Michigan.

Well, the other shoe has dropped here at Penn State. Earlier this month the university announced the details of changes to the health care coverage effective next January 1.* The monthly premium for family coverage is going up 12% (the individual premium is increasing at the same rate), not an unusually large rise given recent history. However, the coverage that Penn State employees receive is changing radically. The university is instituting two types of charges that didn't exist in the past. The first is an annual deductible, something that is common in many other health insurance plans. Families will pay a $500 deductible, which means that the subscriber has to pay the first $500 of health care costs in a year, before the insurance coverage kicks in.

In addition, the university is instituting a co-insurance charge of 10%, meaning that the subscriber is now responsible for paying 10% of all charges, with the health plan paying the remaining 90%, up to a maximum of $2,000 per year (including the deductible) for a family, or $1,000 for an individual. While 10% doesn't sound like much, you have to remember that under our current coverage the plan pays 100% of the costs. Here's a link to the details of the new plan.

Thus, the impact of the deductible and co-insurance charges is that many families will end up paying $2,000 (in addition to their monthly premiums) above and beyond what they're paying this year. The combination of the increase in the premium along with the out-of-pocket additions means that my cost for health care next year is likely to go up by about $2,400. This represents an increase of about 80% in the out-of-pocket costs, not including co-pays. But the co-pays are going up also, so 80% is probably a reasonable estimate of the increase.

Before you run off and blame the federal government's health care overhaul passed earlier this year, for causing these increases, I can comfortably say that that's not the reason. Rather, the university - like many employers - has been struggling with rising health care costs and how to control them over the last couple of decades. This has been a topic discussed in two university-wide panels on which I have served in the last few years, the University Strategic Planning Council, and the current Academic Program and Administrative Services Review Core Council.

The university has taken some steps, such as instituting wellness programs, to try to help control the demand for health care services among its employees. It also waives the co-pay for visits to two local clinics staffed by employees of Penn State's Hershey Medical Center, in order to encourage employees and their families to use these services (at presumably lower cost) than opting to go to other providers or an emergency room for care.

But eventually Penn State must have realized that more of the costs had to be shifted from being borne by the university to being paid by employees. The changes being implemented effectively accomplish this. There are obviously large equity issues at play here. The additional out-of-pocket costs represent a little over 2% of the gross income of a professor or administrator making $100,000, but it's 8% of the income of a secretary making $36,000.

Now that it has instituted deductibles and co-insurance for the first time (at least in the eight years I have been here), it is unlikely that these will ever go away. Penn State employees covered by this plan should realize that they still benefit from health insurance coverage that is probably better and relatively less expensive than what most people in the country have access to. But they should also realize that these costs will continue to rise in the future.

* Last January 1st, the university drastically changed the health care coverage for retirees, with new employees hired after that date receiving a defined contribution health care plan in retirement, while existing employees enjoy a defined benefit health plan. But that's a topic for another day.

A delay on gainful employment, but a commitment to move forward

The Education Department announced yesterday that it was going to delay issuance of some of its gainful employment rules in order to examine more closely some of the 83,000 comments submitted. At the same time it announced that it was still planning on releasing the rest of the rules on November 1, as it had originally planned.

As I wrote in my last post, the for-profit sector had kept the pressure on even after the comment period on the rules was over. In an apparent attempt to improve its image and perhaps sound more like the other sectors of the higher education industry, the Career College Association has just changed its name to the Association of Private-Sector Colleges and Universities, or APSCU, an acronym uncomfortably close to that of AASCU, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Or, as APSCU states on its website, ""CCA is changing because there comes a time when only change can get you where you need to be." I have no idea what that means. The new tagline for the organization is prominently displayed on its homepage:

The notion of providing options to students has been at the crux of the organization's argument against the Department of Education tightening regulations.on the industry. "Committed to putting students first" seems rather facetious given that these are all for-profit companies, and their primary responsibility is to their shareholders, not their customers.

One of the interesting tidbits in the Chronicle of Higher Education's article about the delay was the revelation that Corinthian Colleges, Inc., the company that started the "My Career Counts" public relations campaign I wrote about in my last post, is spending in the "high seven figures" on the campaign. Probably money well spent if Corinthian and APSCU is successful in getting the gainful employment rules delayed, or better yet for them, significantly weakened.

As I wrote in my last post, the for-profit sector had kept the pressure on even after the comment period on the rules was over. In an apparent attempt to improve its image and perhaps sound more like the other sectors of the higher education industry, the Career College Association has just changed its name to the Association of Private-Sector Colleges and Universities, or APSCU, an acronym uncomfortably close to that of AASCU, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Or, as APSCU states on its website, ""CCA is changing because there comes a time when only change can get you where you need to be." I have no idea what that means. The new tagline for the organization is prominently displayed on its homepage:

The notion of providing options to students has been at the crux of the organization's argument against the Department of Education tightening regulations.on the industry. "Committed to putting students first" seems rather facetious given that these are all for-profit companies, and their primary responsibility is to their shareholders, not their customers.

One of the interesting tidbits in the Chronicle of Higher Education's article about the delay was the revelation that Corinthian Colleges, Inc., the company that started the "My Career Counts" public relations campaign I wrote about in my last post, is spending in the "high seven figures" on the campaign. Probably money well spent if Corinthian and APSCU is successful in getting the gainful employment rules delayed, or better yet for them, significantly weakened.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

The for-profits keep the pressure on gainful employment rules

Even though the comment period on the Department of Education's gainful employment rules is over, the for-profit sector is clearly keeping up the fight. This morning's New York Times (Washington edition) has a big, full-page ad (split across two pages) in the front news section (click on the picture to see a larger version of it). Navigating to the URL shown in the ad, www.mycareercounts.org, takes you to a website with all the reasons why the proposed gainful employment rules should be tossed out.

It's a little difficult to figure out who created the website, until you look at the very small print at the bottom of the page:

The website is sponsored by Corinthian Colleges, Inc., one of the nation's largest for-profit higher education providers. A recent report by Education Sector on the impact of the proposed gainful employment rules found that 15 percent of the Corinthian Colleges programs would face restrictions under the rules. The report also noted that the firm had recently reported to analysts that "89 percent of its revenue comes from federal aid programs and only about 1 to 2 percent comes from cash payments from students." Yes, you read that correctly: student payments represented only 1 to 2 percent of the firm's total revenues. Clearly, the loss of eligibility for Title IV federal student aid funds poses a major threat to the firm's continued growth and viability.

Don't be surprised to see continued pressure and lobbying from the for-profit sector, at least until the Department's rules are finalized (due by November 1). The Chronicle of Higher Education reported this week that the industry had given almost $100,000 in campaign contributions in the first seven months of the year to members of Congress who had sent letters to Secretary Duncan asking him to reconsider the rules. Many of these letters are prominently featured on the "My Career Colleges" website. The Chronicle also tallied the hundreds of thousands of dollars in lobbying costs incurred by for-profits this year, an amount that represented a large increase over last year. For example, the article noted that Corinthian Colleges spent $310,000 in lobbying costs in the second quarter of this year, an almost 200 percent increase over last year's $110,000.

[Update] When I finally got around to reading the rest of the Sunday Times, I discovered this full-page ad on the front of the second news section (again, you click to see a larger image):

It's a little difficult to figure out who created the website, until you look at the very small print at the bottom of the page:

The website is sponsored by Corinthian Colleges, Inc., one of the nation's largest for-profit higher education providers. A recent report by Education Sector on the impact of the proposed gainful employment rules found that 15 percent of the Corinthian Colleges programs would face restrictions under the rules. The report also noted that the firm had recently reported to analysts that "89 percent of its revenue comes from federal aid programs and only about 1 to 2 percent comes from cash payments from students." Yes, you read that correctly: student payments represented only 1 to 2 percent of the firm's total revenues. Clearly, the loss of eligibility for Title IV federal student aid funds poses a major threat to the firm's continued growth and viability.

Don't be surprised to see continued pressure and lobbying from the for-profit sector, at least until the Department's rules are finalized (due by November 1). The Chronicle of Higher Education reported this week that the industry had given almost $100,000 in campaign contributions in the first seven months of the year to members of Congress who had sent letters to Secretary Duncan asking him to reconsider the rules. Many of these letters are prominently featured on the "My Career Colleges" website. The Chronicle also tallied the hundreds of thousands of dollars in lobbying costs incurred by for-profits this year, an amount that represented a large increase over last year. For example, the article noted that Corinthian Colleges spent $310,000 in lobbying costs in the second quarter of this year, an almost 200 percent increase over last year's $110,000.

[Update] When I finally got around to reading the rest of the Sunday Times, I discovered this full-page ad on the front of the second news section (again, you click to see a larger image):

Friday, September 17, 2010

Newsflash! Penn state receives an $88 million gift for. . . . .

Penn State announced today the receipt of the largest single gift in its history, $88 million, from alumnus Terrence Pegula and his wife Kim. As one could imagine, a gift of this magnitude coming at a time when the university is facing such constrained resources is a huge boost for the institution.

Pegula made his money in the natural gas business, and evidently had invested much money in the Marcellus Shale, the huge gas field that spreads across parts of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and West Virginia. Earlier this year, East Resources Inc., the privately-held firm of which he was founder, CEO, and a principal shareholder (according to the Penn State press release), was sold for $4.7 billion to Royal Dutch Shell.

The campus is buzzing and the excitement is impalpable as people think about the potential for such a large gift. Well, at least until you read past the headline and discover that the $88 million is going to be used for. . . . hockey. Yes, you read correctly: $88 million for hockey. To be a bit more precise, the money is going to help build a "state-of-the-art, multi-purpose arena," as well as provide operating funds for the men's and women's hockey clubs to move to Division 1 status, according to the press release issued by Penn State today.

Penn State is fortunate in that it has not faced the same kind of funding constraints faced by other public universities, especially those in states such as California, Arizona, Florida, and Nevada. Nevertheless, the last couple of years have forced the university to make some difficult choices, including raising tuition at rates well in excess of inflation, withholding raises and keeping salaries flat last year, and instituting additional cost sharing for health insurance for employees (to be implemented next January 1).

Penn State is not a poor university by any means; according to the Chronicle of Higher Education's endowment database, Penn State had the nation's 45th largest endowment as of June 30, 2009, at $1.23 billion (since increased to $1.4 billion as of last June 30, according to a report provided to the trustees yesterday). A key difference between Penn State and our peers with billiion dollar plus endowments, however, is the size of the university. Penn State's endowment has to support 24 campuses and approximately 90,000 students. Contrast this with Wellesley College, two spots above PSU at number 43, whose endowment of $1.27 billion supports its one campus and 2,324 students. For those who don't want to do the math, this means that Wellesley's endowment per student is 40 times greater than Penn State's.

It is difficult for any university to look the proverbial gift horse (or alumnus, in this case) in the mouth and say, "No thanks" to any gift, particularly one as sizable as this. Those of us who work in universities and study their operation know that when donors get an idea in their heads of what they want to fund, it can often be difficult to get them to consider more pressing needs. I don't know how much the university tried to convince the Pegulas that Penn State had higher priorities than a new ice rink and Division 1 hockey teams. But clearly this was a priority for them, and in a couple of years we'll be able to gaze upon our new "state-of-the-art" hockey rink, right next door to the nation's second largest football stadium, our four year-old baseball stadium (capacity 5,406 and 20 luxury suites), and the now somewhat aged in comparison Bryce Jordan Center.

One can't wonder about what else $88 million could have bought for the university, if the Pegulas had been convinced to invest in the core of the university's business, i.e., teaching and research, rather than intercollegiate athletics. But here are just a few ideas of what $88 million could purchase:

Pegula made his money in the natural gas business, and evidently had invested much money in the Marcellus Shale, the huge gas field that spreads across parts of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and West Virginia. Earlier this year, East Resources Inc., the privately-held firm of which he was founder, CEO, and a principal shareholder (according to the Penn State press release), was sold for $4.7 billion to Royal Dutch Shell.

The campus is buzzing and the excitement is impalpable as people think about the potential for such a large gift. Well, at least until you read past the headline and discover that the $88 million is going to be used for. . . . hockey. Yes, you read correctly: $88 million for hockey. To be a bit more precise, the money is going to help build a "state-of-the-art, multi-purpose arena," as well as provide operating funds for the men's and women's hockey clubs to move to Division 1 status, according to the press release issued by Penn State today.

Penn State is fortunate in that it has not faced the same kind of funding constraints faced by other public universities, especially those in states such as California, Arizona, Florida, and Nevada. Nevertheless, the last couple of years have forced the university to make some difficult choices, including raising tuition at rates well in excess of inflation, withholding raises and keeping salaries flat last year, and instituting additional cost sharing for health insurance for employees (to be implemented next January 1).

Penn State is not a poor university by any means; according to the Chronicle of Higher Education's endowment database, Penn State had the nation's 45th largest endowment as of June 30, 2009, at $1.23 billion (since increased to $1.4 billion as of last June 30, according to a report provided to the trustees yesterday). A key difference between Penn State and our peers with billiion dollar plus endowments, however, is the size of the university. Penn State's endowment has to support 24 campuses and approximately 90,000 students. Contrast this with Wellesley College, two spots above PSU at number 43, whose endowment of $1.27 billion supports its one campus and 2,324 students. For those who don't want to do the math, this means that Wellesley's endowment per student is 40 times greater than Penn State's.

It is difficult for any university to look the proverbial gift horse (or alumnus, in this case) in the mouth and say, "No thanks" to any gift, particularly one as sizable as this. Those of us who work in universities and study their operation know that when donors get an idea in their heads of what they want to fund, it can often be difficult to get them to consider more pressing needs. I don't know how much the university tried to convince the Pegulas that Penn State had higher priorities than a new ice rink and Division 1 hockey teams. But clearly this was a priority for them, and in a couple of years we'll be able to gaze upon our new "state-of-the-art" hockey rink, right next door to the nation's second largest football stadium, our four year-old baseball stadium (capacity 5,406 and 20 luxury suites), and the now somewhat aged in comparison Bryce Jordan Center.

One can't wonder about what else $88 million could have bought for the university, if the Pegulas had been convinced to invest in the core of the university's business, i.e., teaching and research, rather than intercollegiate athletics. But here are just a few ideas of what $88 million could purchase:

- The university could announce attainment of its goal of raising $100 million in its Trustee Matching Scholarship Program. Announced in 2002, the university had achieved 63% of the original goal (as of last November). This is a wonderful program, with the scholarships all going to undergraduates eligible for Pell Grants, meaning they come largely from families with incomes below $50,000. Yet raising the money has been a bit of a struggle for the university. The Pegulas could have allowed the university to reach its $100 million goal and still had plenty left over.

- Roughly 1,500 full-tuition, 4-year scholarships for enternig freshmen this year.

- Roughly 2,500 half-time graduate assistantships this year (stipend and tuition waiver), or tuition waivers for approximately 5,300 graduate assistants

- 88 endowed professorships throughout the university (such as in the Department of Education Policy Studies in the College of Education, to provide just one suggestion)

- An endowment that could fund annually into perpetuity:

-- 300 undergraduate full-tuition scholarships, or

-- 270 graduate tuition waivers

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

One more time on gainful employment

After taking a summer hiatus, The Itinerant Professor is back in full swing. Yes, just like network television shows, this blog takes a summer hiatus. And just like major league baseball stars, it also refers to itself in the third person.

Enough posturing. The big news this fall is the overwhelming response to the proposed gainful employment rules published by the Department of Education in the Federal Register in July. "Overwhelming" as in over 83,000 comments on the rules submitted to the Department, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, far in excess - by scores of thousands - of any other proposed rules by the Department in recent memory .

As Inside Higher Ed pointed out in a recent article, the vast majority of these came in from students, employees, and supporters of for-profit institutions, often coordinated by the Career College Association (CCA), the lobbying arm for the for-profit sector. These were not the result of grass roots efforts, but more akin to the "astroturf" campaigns where companies or other organizations try to make contacts with Congress or federal agencies appear to come from individuals alone, rather than as part of an orchestrated campaign. The IHE article described how Education Management Corp. hired a "Republican-affiliated strategy firm" to encourage and assist employees of its many for-profit institutions to write letters in response to the gainful employment rules. The article noted that the CCA "also coordinated bulk submissions of hundreds of comments."

The story about Education Management Corp. was first published by Stephen Burd of the New American Foundation's Higher Ed Watch blog:

“This week, employees throughout EDMC and our schools will be receiving phone calls during business hours from our partners, the DCI Group, to assist you in crafting personalized letters to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan detailing for him your own views on Gainful Employment,” Todd Nelson, EDMC’s chief executive officer, wrote last Tuesday to the company’s approximately 20,000 employees in an e-mail, which was obtained by Higher Ed Watch.One of the major criticisms of the rules raised by the CCA campaign is that they would likely force many for-profit institutions, or at least some of the programs in those institutions, to close, as students in them would no longer be eligible for federal Title IV student aid funds. The campaign has emphasized how this would severely affect access to higher education by poor and minority students, since they are disproportionately enrolled in this sector. A recent press release by the CCA stated that:

“You will be asked a series of short questions that will help DCI Group create a unique letter. These personalized letters will then be delivered to you for a signature, along with a pre-addressed stamp envelope,” wrote Nelson. “We encourage you to mail the letters as quickly as possible so that your comments are received before September 9. The entire process should take no more than 10 minutes of your time, but its impact on EDMC would be immeasurable.”

By closing programs and placing others in a tenuous “restricted” category, the ED gainful employment proposal has the potential to push 2.3 million students out of higher education, according to a CCA commissioned economic analysis prepared by Charles River Associates. This number includes 790,000 fewer females, 210,000 fewer African-Americans, and 190,000 fewer Hispanics.[In the interest of full disclosure, I should note that the CCA had approached me earlier this year about hiring me to conduct this study for it, but I declined.]

The question now is how the Department is going to react to all these comments. It clearly knows that a good portion of these are the result of the astroturf campaign, and thus, are likely to be discounted in importance. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has been fairly strident in his criticism of the for-profit sector and the need for the gainful employment rules, and has shown little inclination to back down on the preliminary rules published in July.

My guess is that the Department will stand its ground, and attempt to implement the rules largely as published. An early indication of this was the press release issued by the ED earlier this week when it announced the most recent student loan default rates for FY2008, which rose from the previous year - not a great surprise, given the recession. But in releasing the data, Secretary Duncan noted that:

"The data also tells us that students attending for-profit schools are the most likely to default," Duncan continued. "While for-profit schools have profited and prospered thanks to federal dollars, some of their students have not. Far too many for-profit schools are saddling students with debt they cannot afford in exchange for degrees and certificates they cannot use. This is a disservice to students and taxpayers, and undermines the valuable work being done by the for-profit education industry as a whole," Duncan continued.So stay tuned. The Department is scheduled to issue the final rules on November 1, with the rules scheduled to take effect next July 1.

Monday, July 26, 2010

A more detailed analysis of ED's proposed gainful employment rules

Now that I've had a chance to actually peruse (note I didn't say "read," since they are 93 pages long) the Education Department's proposed "gainful employment rules" for proprietary colleges, which were just published in the Federal Register today, I feel a little more qualified to comment on them. Pay attention, folks: comments are due to ED by September 9.

A few interesting observations about the proposed rules:

- Rather than basing eligibility for participation in the federal Title IV (student financial aid) programs solely on loan default rates, as do the current regs, the new rules use a two-part test: loan repayment rates and earnings-to-student loan repayment ratios. Thus, institutions with programs that prepare students for gainful employment (i.e., vocationally-oriented programs) would have to demonstrate that students were both making enough money to pay back their loans, and were actually paying them back at acceptable rates. No jokes please about programs that do not prepare people for gainful employment, i.e., most bachelor's degree programs.

- The application of the default and earnings-to-repayment ratios would result in institutions falling into three categories:

-- Fully eligible to participate in Title IV

-- Ineligible to participate in Title IV

-- Partially eligible, but would have to curtail their growth and provide certain information to consumers about the risks of excessive borrowing

The ED estimates that 5 percent of proprietary institutions would fall into the ineligible category, and 55 percent would become partially eligible.

- The new rules apply not just to proprietary (for-profit) colleges, as much of the press has focused on. They apply to any higher education institution that offers gainful employment programs. The ED estimates that the new regulations will affect the following number of institutions:

-- For-profit: 22.7%, or 474 institutions

-- Private, not-for-profit: 15%, 36 institutions

-- Public: 11.8%, 252 institutions

Note that the percentages are based only on the number of institutions in each sector that offer gainful employment programs. Harvard, for example, would not be included in the denominator of the private, not-for-profit category.

- The Dept. of Education obviously has good data on default rates on federal student loans, from the National Student Loan Data System. But the mystery was where it was going to get the data to calculate the earnings-to-repayment ratios. Would it rely on the institutions to survey their graduates? Would it survey graduates? Or perhaps rely on a third party? Well, the answer is found on page 43623 of the Federal Register:

"The Department would calculate the average annual earnings by using most currently available actual, average annual earnings, obtained from the Social Security Administration (SSA) or another Federal agency,. . ."

So the Department will most likely use Social Security Numbers to match student loan repayment amounts with individual's earnings, as recorded in the Social Security system.

It is too early to tell whether the regulations will survive largely in the form ED has proposed them. One sign that they likely will is that Congress has grabbed onto this issue and doesn't appear ready to let go. So some form of tighter rules will likely occur, and how much teeth they have will be determined in large part by the lobbying (and political donation) strength of the for-profit sector.

Stay tuned.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Department of Education finally issues the gainful employment rules for proprietary colleges

The ED finally issued the rules for measuring gainful employment in proprietary colleges. The rules will impose a two-part test for gradutes of vocational programs, involving both earnings-to-loan repayment ratios, as well as default rates. ED estimates that under the rules, 5 percent of proprietaries will be forced out of the Title IV federal student aid programs entirely, and another 55 percent will see their growth restricted by the regs.

Marketplace covered it this morning, including a short quote from me (here's a link to the audio of the story), as did the Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Businessweek publishes an embarrassingly bad article on the college wage premium

Bloomberg Businessweek published a "special report" on the return on investment to individual colleges that can charitably be described as misleading at best, irresponsible at the worst. Titled "College: Big Investment, Paltry Return," the article purports to demonstrate how students attending some colleges earn a higher return on their investment than students attending other colleges. Businessweek used a consulting firm that collected self-reported salary information on its website, and used that salary information to calculate the median earnings for graduates of each college, and compares this to what people who only have high school diplomas earn.

The consulting firm then subtracted the current cost of attendance for each institution, adjusts for the school's six-year graduation rate, and used the result to calculate an expected annual ROI over 30 years. And as is ever so popular these days, it creates a ranking of 554 4-year colleges and universities across the country, from highest to lowest ROI (the methodology is described here). The results? MIT has the highest ROI in the country at 12.6%, and Black Hills State University (in South Dakota) the lowest, 4.3%. The article also publishes a shame list, or those schools with high tuition but a low ROI.

So what's wrong with this "special report"? Here are just a few examples:

- Probably the most egregious error is that the article makes the same mistake so many articles in the popular press make: it confuses correlation with causality. The article implies that any random student out there attending a higher-ranked institution will have a higher ROI than attending a lower-ranked one. But of course students are not randomly distributed across those 852 institutions. If you took all the MIT students, and sent them to Black Hills State University, the Black Hills ROI would skyrocket. Why? Because the typical MIT student has a higher level of human capital (intelligence, skills, aptitude, motivation - whatever you want to call it) than does the average student attending Black Hills State.

So MIT may very well impart some added value on its attendees, as I'm sure it does, but it can't claim the full credit for their post-college earnings. Another way to think of it is to consider an experiment. Take all those students who were admitted to MIT and Black Hills, and randomly assign some of the students to attend their chosen institution, and others to not be allowed to enroll and instead go into the labor markets without the benefit of a college degree. Under Businessweek's methodology, one would expect all of those non-college attendees to have the same earnings. But of course this wouldn't be true; the students admitted to MIT but not allowed to attend would likely have much higher earnings in labor markets even without attending college than would the students accepted to Black Hills but not attending. This is because many of the same traits that got those students admitted to MIT are also valued in labor markets and thus rewarded through higher wages.

In statistical terms, the Businessweek methodology suffers from strong selectivity bias effects.

- The earnings data used in the study are entirely self-reported on the consulting firm's website, and is by no means guaranteed to be representative of the population of graduates of each institution. Thus, the earnings data used in the calculations could very well be biased upward or downward - there is no way to tell.

- The cost-of-attendance data used in the study are based on sticker prices, and don't account for financial aid students receive. Given the important role that institutional financial aid plays in subsidizing the cost of college today (see for example this study I did a few years ago, or more recently a study with my Penn State colleagues John Cheslock, Rodney Hughes, and Rachel Frick-Cardelle), the lack of accounting for institutional aid leads to downwardly biased ROI figures for many institutions.

- The ROI figures are going to be highly dependent upon the mix of majors in each college. Thus, Businessweek's list of "best bargains" is skewed toward public institutions that enroll a large number of students in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields, i.e., Colorado School of Mines, Georgia Tech, Virginia Tech, Cal Poly, Purdue, and Missouri University of Science & Technology.

- It has been well documented that jobs that require college degrees generally have much better benefits, particularly pension and health care benefits, than those held by people with only a high school diploma. Thus, by focusing on earnings only, and not accounting for benefits differences, the returns to college are again biased downward.

The article concludes with this ridiculous comment:

Over the past 30 years, the S&P 500 Index averaged about 11 percent a year. Only 88 schools out of the 554 in the study had a better return than the S&;P. Everywhere else, students would have been better off—financially, at least—if they invested the money they spent on their college educations and never set foot in a classroom.So the message here is that unless you attend one of those 88 schools, you are better off skipping college and instead investing the money in the stock market.

"For almost every school on the list," writes Lee [the director of quantitative analysis at the consulting firm used by Businessweek] in an e-mail, "prospective students paying full price would probably have been better off investing in the stock market 30 years ago rather than spending their money on a college education."

There have been many egregious examples over the years of the misuse of quantitative data to create rankings of colleges and universities. But this is perhaps the worst I have ever seen.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Glenn Beck University

I was (briefly) interviewed on Marketplace Morning Report this morning about Glenn Beck's new "university."

Friday, May 28, 2010

A spitting contest on HuffPost

Okay, I really wanted to title this, "A pissing contest," or worst case, "A urinating contest," but decided that was not decorous and dignified enough for The Itinerant Professor. So I toned it down a notch.

Michele Hernandez, admissions consultant extraordinaire of whom I previously wrote, published a piece in HuffPost yesterday blaming Harvard for hyping the admissions market for selective institutions. Far be it from me to defend Harvard; I've been plenty critical of the institution in this blog (just do a search for "Harvard" in the search box). I wrote a comment to her post stating that she was playing loose with the facts, and that she and her industry were as much to blame for the frenzy and anxiety students and parents face when dealing with trying to get in to these institutions. She then responded, and. . . .well, you can guess where this is going. She accused me of directing "anger" toward her, which was (I thought) not my tone at all. Guess some people believe anytime you disagree with them you're showing anger.

For some reason, HuffPost deleted parts of my response, I think because I posted too many times. So I'm reprinting the entire thing here:

Michele,

There is no "anger" whatsoever in my original comment; I didn't intend it as a wild rant, and if it came across that way, I apologize [I usually keep my angry rants anonymous :) ]. I'm merely questioning some of the facts you provided in your post, along with your assumption about where the admissions frenzy comes from. I questioned in your original post when you said that students were applying to 15-30 schools a year. You said in your comment that "My data is not based on anecdotes but rather on the actual data provided by colleges." I think you need to provide some citation for these numbers. I recognize HuffPost is not a scholarly journal, but there is still an obligation to inform your readers where these numbers come from.

My suspicion is that your "15-30 schools a year" is a wild exaggeration that is not based on reality, but based on the frenzy created at least in part by the admissions industry, as well as by the media. How many students are really applying to this many schools?

The U.S. Department of Education conducted a nationally-representative survey of students graduating from high schools in the U.S. in 2004; this survey found that only one-half of one percent of graduating seniors applied to 11 or more schools. Even allowing for the changes in college admissions that have occurred since 2004, due to Harvard's dropping of ED and other changes you describe, you would still be a long way from a norm of students today applying to 15-30 schools. Yes, there may be a very small number who do this, but to put this out there as the norm for those applying to the most selective schools I would describe as fear-mongering.

You are right that the colleges are to blame in part for this frenzy, as well as the media as I said earlier, but I believe the admissions consultant industry (of which you are certainly a very prominent member) is at least equally to blame. You try to convince parents that the only way to get their children into one of these institutions is by using the insider knowledge that you and others have, and that without that information (and the often five-figure fee that obtains it), their child has a snowball's chance in Miami of getting into one of those colleges. The fact that you state that “I turn away almost as many students as I work with” is no defense of what your industry helped to create.

In last year’s article in The New York Times (July 18 2009) on the admissions consultant industry, you were quoted as saying: "‘It’s annoying when people complain about the money,’ the Vermont-based counselor, Michele Hernandez, said. ‘I’m at the top of my field. Do people economize when they have a brain tumor and are looking for a neurosurgeon? If you want to go with someone cheaper, or chance it, don’t hire me.’" Is this really the impression we want to send to parents and prospective students, that getting into college is as complicated – and dangerous – as brain surgery?

Another way you add to the frenzy is through the impression you and some in your industry help to promulgate that the Ivy League institutions (and the small handful of others with similarly low acceptance rates) are the only reasonable destination for bright, motivated students. This does a terrible disservice to many students who could and would receive an excellent undergraduate education, often better than they would receive at one of these low-admittance schools, at many of dozens of other schools around the country that have much more reasonable acceptance rates and sometimes lower costs (see the work of The Education Conservancy – http://educationconservancy.org – for helping to combat this). I imagine you’ll respond by saying that that’s part of your service, to help students find the right schools for them. But it’s hard to deny that your website and publicity emphasizes the Ivies, and by featuring so prominently their low acceptance rates, you help add to the anxiety and insecurity these families face.

We'll have to wait and see if she responds.

The Itinerant Professor curse

Well, just as I was writing something nice about the proprietary sector, word comes out that an influential analyst has trashed it. Steve Eisman of FrontPoint Financial Services Fund, an analyst featured in Michael Lewis's book The Big Short, spoke at the Ira Sohn Investment Research Conference on Wednesday. He was quoted as saying (by Inside HigherEd):

Mother Jones has a good recap of Eisman's perspective on the sector, and why he thinks it's ready for a tumble. He blames the Obama administration's push for gainful employment regulations, which would force the sector to demonstrate that graduates of their institutions make enough money to shoulder the higher debt burdens students there have, on average (see the recent College Board report, Who Borrows Most? for more on this issue).

Criticism of this sector is not new; as far back as almost two decades ago, in the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education of 1965, the regulations on student loan defaults were changed and hundreds of proprietary institutions were thrown out of the Title IV programs. But the sector has demonstrated an incredible resilience - and profitability - over the years. The Chronicle of Higher Education had been doing a good job tracking the share prices and market cap of the key players in the sector, but it seemed to have stopped this in recent years (here's the most recent article on it I could find, from 2008 - you need to be a Chronicle subscriber to read it). Its reporting has shown how stock prices of many of the large companies, such as Apollo Group (parent company of the University of Phoenix, the 640 pound gorilla in the industry), ITT Tech, Capella, and others, have risen far in advance of most market indices over the last decade (and fell less rapidly in the decline of the last couple of years).

Many in the proprietary sector broke out the champagne, I'm sure, when Bob Shireman announced last week that he was leaving the Department of Education. He was seen as the leader of the efforts to rein in the sector, which has seen its share of Pell Grant dollars increase to 21 percent, even though they represent 9 percent of undergraduate enrollment (data from the College Board Trends in Student Aid website). Their glee may be shortlived, however. It is likely that others in the Department, as well as Congress, will continue the scrutiny of which Shireman was the figurehead. Steve Eisman obviously agrees.

"Until recently, I thought that there would never again be an opportunity to be involved with an industry as socially destructive and morally bankrupt as the subprime mortgage industry," said Eisman. "I was wrong. The For-Profit Education Industry has proven equal to the task."Pretty strong words from someone who supposedly has a good track record for reading markets and industries.

Mother Jones has a good recap of Eisman's perspective on the sector, and why he thinks it's ready for a tumble. He blames the Obama administration's push for gainful employment regulations, which would force the sector to demonstrate that graduates of their institutions make enough money to shoulder the higher debt burdens students there have, on average (see the recent College Board report, Who Borrows Most? for more on this issue).

Criticism of this sector is not new; as far back as almost two decades ago, in the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education of 1965, the regulations on student loan defaults were changed and hundreds of proprietary institutions were thrown out of the Title IV programs. But the sector has demonstrated an incredible resilience - and profitability - over the years. The Chronicle of Higher Education had been doing a good job tracking the share prices and market cap of the key players in the sector, but it seemed to have stopped this in recent years (here's the most recent article on it I could find, from 2008 - you need to be a Chronicle subscriber to read it). Its reporting has shown how stock prices of many of the large companies, such as Apollo Group (parent company of the University of Phoenix, the 640 pound gorilla in the industry), ITT Tech, Capella, and others, have risen far in advance of most market indices over the last decade (and fell less rapidly in the decline of the last couple of years).

Many in the proprietary sector broke out the champagne, I'm sure, when Bob Shireman announced last week that he was leaving the Department of Education. He was seen as the leader of the efforts to rein in the sector, which has seen its share of Pell Grant dollars increase to 21 percent, even though they represent 9 percent of undergraduate enrollment (data from the College Board Trends in Student Aid website). Their glee may be shortlived, however. It is likely that others in the Department, as well as Congress, will continue the scrutiny of which Shireman was the figurehead. Steve Eisman obviously agrees.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Building linkages with the proprietary sector?

A couple of weeks ago I attended a meeting at the American Enterprise Institute titled "AEI Forum on Higher Education." From the invitation, it was a little unclear what the focus of the meeting was going to be. But given that it was being sponsored by AEI, my assumption was that it was going to revolve around something to do with markets and market forces in higher education, given AEI's fairly conservative orientation. My first thought was, "Are you sure you want me there?", but I figured it could make for an interesting event so I agreed to attend.

The meeting did, in fact, focus on markets in the sense that there was a heavy does of proprietary sector institutions and other companies represented. It was a small group of people, only about 25 or so, including (I believe) just five of us "traditional" academics. We've been asked not to divulge the details of what was discussed at the meeting, as it was designed to create an open dialogue between the participants, and make some connections between those of us on the traditional (i.e., public or not-for-profit institutions) and for-profit sides.

What I can say was that it was interesting hearing people from the proprietaries talking in detail about some of what goes on in their institutions. I've read quite a bit about this sector, and have heard bits and pieces at conferences, but not to this level of detail before. I've also written some about my interactions with this sector.before. The meeting also included representatives from companies that were not direct postsecondary providers, like some of the institutions whose logos I included at the top of this post. These other companies provide a variety of services to both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions alike.

Part of AEI's agenda for the meeting was tto spur more research on the new providers in higher education. It's unclear yet where this will go, but there is at least one lead I am following up on with one company. Stay tuned for more details.

Thursday, April 29, 2010

The 21st Century Student: Can American Colleges Deliver?

Here's a link to the summary (and streaming audio) of a talk I gave last week in Penn State's Research Unplugged lecture series.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

It's not easy making up $11B in endowment value

Yes, it's come down to this -- Harvard now begging its alumni to send their spare change to Cambridge to help it recover the $11B (or 27%) in endowment value it lost last year. Okay, that's just a little bit of an exaggeration - they're asking for more than just spare change. But the impact of the downturn in Harvard's endowment is being felt across the university. It's easy to take potshots at what Boston Globe columnist Alex Beam used to lovingly refer to as World's Greatest University, or WGU for short (not to be confused, of course, with the Western Governors University, a somewhat less-prestigious on-line university). But maybe some of those potshots are deserved.

Harvard flew high in the 1990s and in the early part of the current century, when it often earned annual returns in the high teens, with an endowment heavily-invested in private equity and other alternative investments. It is easy to simply write off last year's plunge as the inevitable result of the crows coming home to roost - that in return for earning double-digit returns all those years, the university exposed itself to such high betas that it ran the risk of a large downturn at some point. And in fact, Harvard Management Company has trumpeted this perspective, arguing that if it had invested its endowment more conservatively all those years, and had earned returns much closer to market benchmarks, then it would never have grown as spectacularly as it did: "Harvard's long-term performance remains strong, even after the severe market correction experienced in fiscal year 2009. The 10-year annualized return is 8.9% versus 1.4% for a typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio." That 8.9% still sounds good, but keep in mind that just two years earlier the 10-year annualized return had been 15%.

But this just may be a bit of Monday morning quarterbacking on Harvard's part. Yes, by investing in risky instruments with higher betas, Harvard did earn larger returns. And it turned around and took those earnings and plowed them into the operating budget (Harvard subsidizes about 40% of its operating budget through endowment earnings). But it took this action with likely little forethought to what would happen to the operating budget if those endowment earnings plummeted, as they did last year. The result is that Harvard now has a mess on its hands, as signified by large holes in the ground across the Charles River in Boston where it has halted construction on the Allston campus (see these articles from Harvard Magazine, "Allston Development on Ice" and "Arrested Development"). Harvard also had to borrow $2.5 billion in December 2008 in order to meet cash needs and to meet calls on private equity investments.

It will take Harvard a long time to return the endowment (and its subsidy of the operating budget) to levels it enjoyed just a couple of years ago. And hopefully Harvard's endowment managers (and those of other universities who made similar investing decisions) will have learned a valuable lesson about the downside of risky investment instruments.

Harvard flew high in the 1990s and in the early part of the current century, when it often earned annual returns in the high teens, with an endowment heavily-invested in private equity and other alternative investments. It is easy to simply write off last year's plunge as the inevitable result of the crows coming home to roost - that in return for earning double-digit returns all those years, the university exposed itself to such high betas that it ran the risk of a large downturn at some point. And in fact, Harvard Management Company has trumpeted this perspective, arguing that if it had invested its endowment more conservatively all those years, and had earned returns much closer to market benchmarks, then it would never have grown as spectacularly as it did: "Harvard's long-term performance remains strong, even after the severe market correction experienced in fiscal year 2009. The 10-year annualized return is 8.9% versus 1.4% for a typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio." That 8.9% still sounds good, but keep in mind that just two years earlier the 10-year annualized return had been 15%.

But this just may be a bit of Monday morning quarterbacking on Harvard's part. Yes, by investing in risky instruments with higher betas, Harvard did earn larger returns. And it turned around and took those earnings and plowed them into the operating budget (Harvard subsidizes about 40% of its operating budget through endowment earnings). But it took this action with likely little forethought to what would happen to the operating budget if those endowment earnings plummeted, as they did last year. The result is that Harvard now has a mess on its hands, as signified by large holes in the ground across the Charles River in Boston where it has halted construction on the Allston campus (see these articles from Harvard Magazine, "Allston Development on Ice" and "Arrested Development"). Harvard also had to borrow $2.5 billion in December 2008 in order to meet cash needs and to meet calls on private equity investments.

It will take Harvard a long time to return the endowment (and its subsidy of the operating budget) to levels it enjoyed just a couple of years ago. And hopefully Harvard's endowment managers (and those of other universities who made similar investing decisions) will have learned a valuable lesson about the downside of risky investment instruments.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

The latest from the chutzpah department

Sometimes you just have to be amazed at the emails you get from strangers. Here's the latest:

Yeah, right -- some stranger from a for-profit college (which is what it was) wants me to advertise and promote her college for her in my blog, all just because I'm a nice guy. You'd think she'd at least offer me some monetary compensation for the free advertising. But noooooooo. . . .

Let me know if any of you other bloggers have heard from Genevieve.

Don,

I have been perusing educational blogs of late and really enjoy your perspectives on education. I was particularly interested in your post on college campus violence, as there will be a Board of Regents meeting on the University of Colorado Denver campus that is expected to deal with whether or not individuals will be able to bear arms on campus this upcoming week.

Anyway, I work in affiliation with _______ College (www._______.edu) and was wondering if it would be possible for us to place an in-text link to the website in one of your posts? We would not be asking that ________ appear in the text, but rather a link from an anchor text statement would link to ________.

Please email me back and let me know if that is a possibility!

Thanks

Genevieve

Yeah, right -- some stranger from a for-profit college (which is what it was) wants me to advertise and promote her college for her in my blog, all just because I'm a nice guy. You'd think she'd at least offer me some monetary compensation for the free advertising. But noooooooo. . . .

Let me know if any of you other bloggers have heard from Genevieve.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Signs of the apocalypse, part 2

In a long overdue post, I'll describe another sign of the pending apocalypse in higher education. In my earlier post, I described how the State of California is letting its once-vaunted public higher education system die a slow death. This time I turn to Florida, another state that has been battered by the recession and whose higher education system has also taken a beating.

Florida cut its funding for higher education by almost 10 percent this year compared to fiscal year 2009, about three times the size of the average reduction across the nation. The public colleges and universities in the state responded in different ways to the cuts, including gaining the authority from the legislature to raise tuition at a higher rate than they had in the past.

Florida State University announced last month that it was laying off 36 tenure-line faculty, 21 of whom already hold tenure. Traditionally, universities have not laid off tenured faculty without declaring a state of financial exigency, defined by the American Association of University Professors as, "an imminent financial crisis that threatens the survival of the institution as a whole and that cannot be alleviated by less drastic means." While the cuts endured by Florida State are unarguably large, it is hard to make the argument that they threaten the "survival of the institution as a whole."

In discussing the procedures for laying off tenured faculty, the AAUP says, "As a first step, there should be a faculty body that participates in the decision that a condition of financial exigency exists or is imminent, and that all feasible alternatives to termination of appointments have been pursued." The decisions at FSU evidently came from the top down, with very little (if any) faculty input.

Florida State is not the first major university to layoff tenured faculty. Following Hurricane Katrina, Tulane laid off 230 faculty members, 65 of whom were tenured, when it eliminated four of its six engineering departments. But in the wake of the hurricane, which shut the campus for an entire semester, Tulane did declare a financial exigency. The leadership of the university consulted an advisory panel of faculty members in making the decision to eliminate the positions. Even under these circumstances, however, Tulane was criticized by the AAUP and others for going too far.

Florida State, like any other university, is not obligated to adhere to AAUP principles. But AAUP documents such as the 1940 Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure have long been considered "common law" in American higher education. It is likely that other universities will use the current financial situation as an excuse to abandon these principles. Yet it is even more important in times like these that faculty involvement in critical decisions be reaffirmed and valued.

Florida cut its funding for higher education by almost 10 percent this year compared to fiscal year 2009, about three times the size of the average reduction across the nation. The public colleges and universities in the state responded in different ways to the cuts, including gaining the authority from the legislature to raise tuition at a higher rate than they had in the past.

Florida State University announced last month that it was laying off 36 tenure-line faculty, 21 of whom already hold tenure. Traditionally, universities have not laid off tenured faculty without declaring a state of financial exigency, defined by the American Association of University Professors as, "an imminent financial crisis that threatens the survival of the institution as a whole and that cannot be alleviated by less drastic means." While the cuts endured by Florida State are unarguably large, it is hard to make the argument that they threaten the "survival of the institution as a whole."

In discussing the procedures for laying off tenured faculty, the AAUP says, "As a first step, there should be a faculty body that participates in the decision that a condition of financial exigency exists or is imminent, and that all feasible alternatives to termination of appointments have been pursued." The decisions at FSU evidently came from the top down, with very little (if any) faculty input.

Florida State is not the first major university to layoff tenured faculty. Following Hurricane Katrina, Tulane laid off 230 faculty members, 65 of whom were tenured, when it eliminated four of its six engineering departments. But in the wake of the hurricane, which shut the campus for an entire semester, Tulane did declare a financial exigency. The leadership of the university consulted an advisory panel of faculty members in making the decision to eliminate the positions. Even under these circumstances, however, Tulane was criticized by the AAUP and others for going too far.

Florida State, like any other university, is not obligated to adhere to AAUP principles. But AAUP documents such as the 1940 Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure have long been considered "common law" in American higher education. It is likely that other universities will use the current financial situation as an excuse to abandon these principles. Yet it is even more important in times like these that faculty involvement in critical decisions be reaffirmed and valued.

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Signs of the apocalypse, part 1

This week I had the opportunity to testify at a heaing of the Joint Committee on the Master Plan for Higher Education of the California Legislature. This hearing, on Affordability and Student Aid, was the third held by the committee, which is conducting its work as the Master Plan celebrates its 50th anniversary.

In a post on the blog 21st Century Scholar, written before this hearing, I questioned whether the Master Plan -- widely recognized as having created the best public higher education system in the country -- was in fact dead. The State of California has managed to get itself in such a fiscal mess that it is unlikely that it can ever pull itself out. It's not fair to just blame the current recession, which admittedly has battered California as much as any state. The fiscal problems, however, are symptomatic of a three-decade long antitax movement in California that has made it difficult for the legislature and governors to come up with enough funds to adequately fund the University of California, California State University, and the state's community colleges.

I'm sorry to report that, after sitting through part of the hearing this week, it is unlikely that this Joint Committee is going to be able to resolve the problems facing higher education in California. It is clear that the fiscal constraints facing the state are unlikely to be removed without large-scale changes to the political structures there. This would include changing laws and initiative petitions that have restricted the ability of the legislature and governors to raise the tax revenues necessary to support a world-class higher education system. It would likely also require changing the earmarking of parts of the state budget to purposes such as K-12 education and corrections, both of which leave little flexibility for funding higher education when federal mandates such as Medicaid spending are taken into account.

I'm afraid that the reality is that the future will bring two things. First, public higher education in California will be more expensive for this and future generations of Californians than those who had benefited from the first four decades or so of the Master Plan. While UC and CSU have taken steps to make institutional grants available to financially-needy students (to supplement those funds available through Cal Grants and federal aid), it will likely be a challenge for them to maintain these commitments down the road. Like many other public institutions, they will face immense pressure to address issues of middle-income (and even upper-income) affordability, at the expense of maintaining a commitment to access for poorer students. In a piece I wrote for The Century Foundation in 2003, I demonstrated how the most selective campuses of the UC system did a better job enrolling Pell Grant recipients than their peers around the country. It is unlikely they will be able to continue this commitment in the future.

Second, the three sectors are likely to face a Hobson's choice of either allowing the quality of their institutions to degrade, or to restrict access. I point out in my testimony that six of the UC campuses are ranked in the top 50 national universities, public and private, by U.S. News & World Report, and in the top 200 internationally by the Times Higher Education in London. Starved of the necessary resources to maintain this level of quality, it will have to decrease. Alternatively, the institutions could maintain quality, but at the expense of enrolling fewer students. In the worst case scenario, quality would erode and access would be constricted.

I don't envy the task in front of the Joint Committee, or that of the administrators and faculty in the three sectors in California. There are no easy solutions, other than going back to the public and voters in California and presenting them with the likely outcome if the existing antitax mentality continues. And I am afraid of how the public will react to that proposition.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Another insult to the Canadians

This is not exactly about higher education, but file it under the "Itinerant" part of this blog. Returning from testifying in front of the California legislature (which will be the subject of another post in the not-too-distant future), I picked up the Hemispheres magazine on the United flight. There I found a nice article about what to do in Montreal. At the end of the article, there was this map (click on the map to see a larger version):

Where the Hemispheres map shows Montreal is actually Kingston, ON. Once again, we Americans demonstrate our ignorance of our neighbor to the north. You can download a PDF version of the magazine article on the Hemispheres website.

Notice the small inset map, showing the position of Montreal in Canada and relative to the U.S.

Unfortunately, the map is not even close to where Montreal truly is, as shown in Google maps:

Where the Hemispheres map shows Montreal is actually Kingston, ON. Once again, we Americans demonstrate our ignorance of our neighbor to the north. You can download a PDF version of the magazine article on the Hemispheres website.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Another shooting on campus

There have been too many instances of gun violence on college campuses in recent years. This is obviously a reflection of our larger society, as I have previously written about. But this particular incident hits very close to home, as University of Alabama Huntsville biology professor Any Bishop has been charged with shooting five of her colleagues and a staff member in the biology department at UAH. Three people were killed and three others were injured and hospitalized. The shooting, which occurred Friday afternoon at a meeting of the biology faculty, allegedly involved a dispute over Professor Bishop's tenure. According to news reports, she was denied tenure last year, and apparently an appeal to the department was about to be or had recently been denied. Here are links to stories in The New York Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and Inside Higher Ed.